When tensions flare, people will start using the more charged words more frequently. The obvious counterpart to "negro" in this context is "nigger." It could be used by white racists, non-racists who are quoting or decrying white racists, by blacks trying to "re-claim" the term, by those debating whether or not the term should be used in any context, and so on. Basically, when racial tension is relatively low, these arguments don't come up as often, so the word won't appear as often.

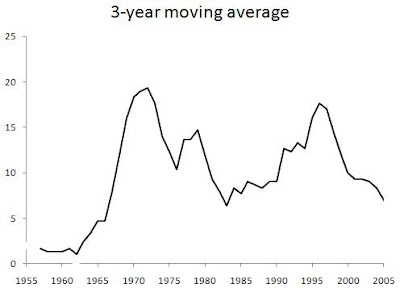

I've searched the NYT back to 1852 and plotted how prevalent "nigger" was in a given year, though smoothing the data out using 5-year moving averages (click to enlarge):

We see high values leading up and throughout the Civil War, a comparatively lower level during Reconstruction, followed by two peaks that mark "the nadir of American race relations." It doesn't change much going through the 1920s, even though this is the period of the Great Migration of blacks from the South to the West and Northeast. It falls and stays pretty low during the worst part of the Great Depression, WWII, and the first 10 years after the war. This was a period of increasing racial consciousness and integration, and the prevalence of "negro" in the Crimson was increasing during this time as well. That means that there was a greater conversation taking place, but that it wasn't nasty in tone.

However, starting in the late 1950s it moves sharply upward, reaching a peak in 1971. This is the period of the Civil Rights movement, which on an objective level was merely continuing the previous trend of greater integration and dialogue. Yet just as we'd guess from what we've studied, the subjective quality of this phase of integration was much more acrimonious. Things start to calm down throughout the '70s and mid-'80s, which our study of history wouldn't lead us to suspect, but which a casual look at popular culture would support. Not only is this a period where pop music by blacks had little of a racial angle -- that was also true of most of the R&B music of most of the '60s -- but was explicitly about putting aside differences and moving on. This is most clearly shown in the disco music scene and its re-birth a few years later during the early '80s dance and pop music scene, when Rick James, Prince, and above all Michael Jackson tried to steer the culture onto a post-racial course.

But then the late '80s usher in a resurgence of identity politics based on race, sex, and sexual orientation ("political correctness," colloquially). The peak year here is technically 1995, but that is only because of the unusual weight given to the O.J. Simpson trial and Mark Fuhrman that year. Ignoring that, the real peak year of the racial tension was 1993 according to this measure. By the late '90s, the level has started to plummet, and the 2000s have been -- or should I say were -- relatively free of racial tension, a point I've made for awhile but that bears repeating since it's not commonly discussed.

Many people mention Obama's election, but that was pretty late in the stage. Think back to Hurricane Katrina and Kanye West trying but failing to foment another round of L.A. riots, or Al Sharpton trying but failing to turn the Jena Six into a civil rights cause celebre, or the mainstream media trying but failing to turn the Duke lacross hoax into a fact that would show how evil white people still are. We shouldn't be distracted by minor exceptions like right-thinking people casting out James Watson because that was an entirely elite and academic affair. It didn't set the entire country on fire. The same is true for the minor exception of Larry Summers being driven out of Harvard, which happened during a remarkably feminism-free time.

Indeed, it's hard to recognize the good times when they're happening -- unless they're fantastically good -- because losses loom larger than gains in our minds. Clearly racial tensions continue to go through cycles, no matter how much objective progress is made in improving the status of blacks relative to whites. Thus, we cannot expect further objective improvements to prevent another wave of racial tension.

Aside from the long mid-20th C hiatus, there are apparently 25 year distances between peaks, which is about one human generation. If the near future is like most of the past, we predict another peak around 2018, a prediction I've made before using similar reasoning about the length of time separating the general social hysterias that we've had -- although in those cases, just going back to perhaps the 1920s or 1900s, not all the way back to the 1850s. Still, right now we're in a fairly calm phase and we should enjoy it while it lasts. If you feel the urge to keep quiet on any sort of racial issues, you should err on the side of being more vocal for right now, since the mob isn't predicted to come out for another 5 years or so, and the peak not until 10 years from now. As a rough guide to which way the racial wind is blowing, simply ask yourself, "Does it feel like it did after Rodney King and the L.A. riots, or after the O.J. verdict?" If not, things aren't that bad.

Looking at absolute levels may be somewhat inaccurate -- maybe all that counts is where the upswings and downswings are. So I've also plotted the year-over-year percent change in how prevalent "nigger" is, though this time using 10-year moving averages to smooth the data out because yearly flucuations up or down are even more volatile than the underlying signal. In this graph, positive values mean the trend was moving upward, negative values mean it was moving downward, and values close to 0 mean it was staying fairly steady:

Again we see sustained positive growth during the Civil War, the two bookends of the nadir of race relations, although we now see a small amount of growth during the Harlem Renaissance era. The Civil Rights period jumps out the most. Here, the growth begins in the mid-1940s, but remember that it was at its lowest absolute levels then, so even the modest increases that began then show up as large percent increases. The PC era of the late '80s through the mid '90s also clearly shows up. There are several periods of relative stasis, but I see three periods of decisively moving against a nasty and bitter tone in our racial conversations: Reconstruction after the Civil War (admittedly not very long or very deep), the late '30s through WWII, and the "these are the good times" / Prince / Michael Jackson era of the mid-late '70s through the mid '80s, which is the most pronounced of all.

That trend also showed up television, when black-oriented sitcoms were incredibly popular. During the 1974-'75 season, 3 of the top 10 TV shows were Good Times, Sanford and Son, and The Jeffersons. The last of those that were national hits, at least as far as I recall, were The Cosby Show, A Different World, Family Matters, The Fresh Prince of Bel-Air, and In Living Color, which were most popular in the late '80s and early '90s. Diff'rent Strokes spans this period perfectly in theme and in time, featuring an integrated cast (and not in the form of a "token black guy") and lasting from 1978 to 1986. The PC movement and its aftermath pretty much killed off the widely appealing black sitcom, although after a quick search, I see that Disney had a top-rated show called That's So Raven in the middle of the tension-free 2000s. But it's hard to think of black-focused shows from the mid-'90s through the early 2000s that were as popular as Good Times or The Cosby Show.

But enough about TV. The point is simply that the academic material we're taught in school usually doesn't take into account what's popular on the radio or TV -- the people's culture only counts if they wrote songs about walking the picket line, showed that women too can be mechanics, or that we shall overcome. Historians, and people generally, are biased to see things as bad and getting worse, so they rarely notice when things were pretty good. But some aspects of popular culture can shed light on what was really going on because its producers are not academics with an axe to grind but entrepreneurs who need to know their audience and stay in touch with the times.