Moving on, here is a much more detailed follow-up to a GNXP article I wrote about the slowing of innovation after the government downsized or busted up the two main sources of invention in recent times -- AT&T's Bell Labs and the Department of Defense -- over concerns about monopolistic entities. Try to think of something invented after Bell Labs was broken up in 1984 - '85, and that would pass the "telling your grandkids" test. Is it something they will continue to use, or if not, something they would still find really neat? The compilers of "lists of really important inventions" truly struggle to come up with such things invented in the last 25 years, and typically they're highly derivative of other entries -- for example, including not just the cell phone, but the digital cell phone, and even the particular model of the iPhone!

Now let's put this decline in a greater historical perspective. After all, perhaps we could only expect to have one really good run, this run happened in the mid-to-late 20th C., and that's it. Something like the technological Renaissance. Well, we'll see. In contrast to the book that I used before -- Big Ideas: 100 Modern Inventions that have Transformed Our World -- there's a new book out called 1001 Inventions that Changed the World. Instead of starting in 1940, it begins far back into human evolution, including stone tools, clothing, and so on. Plus, it obviously has 10 times as many data-points. There isn't a whole lot before the Common Era, so I've restricted the dates to lie between 0 and 2008 A.D., leaving 855 data-points. (It took a few trips to Barnes & Noble to copy them all down!) It's written by several authors, so there is little chance that the entries reflect an eccentric's view. Flipping through it, just about everything made sense (again, with the exceptions of some desperate attempts to include very recent inventions).

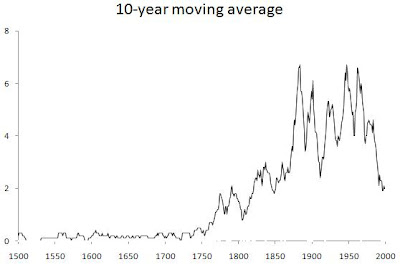

It's not clear what the time scale should be for technological change, so I've included time series graphs at several time scales. They all show roughly the same picture, although fitting a model to these data would show less error in some rather than others. The time intervals are century, half-century, decade, year, and a 10-year moving average of the yearly data to smooth them out. The points for century, half-century, and decade are plotted at the mid-point of the interval (e.g., at 1825 for the decade of the 1820s). The y-axis measures count of inventions. Here are the results (click to enlarge):

If you just looked at the century-scale data, things would look pretty good! Starting in the Early Modern period, there's an accelerating increase that really takes off during the Industrial Revolution and apparently continues straight through the 20th C. Sure, the most recent increases shows diminishing returns, but maybe we just had a mediocre century and things will bounce back.

Unfortunately, zooming in to just the half-century-scale data gives us reason to be pessimistic. Here we see an S-shaped curve (such as the logistic) that clearly shows a near-saturation of the rate of invention. Focusing even closer to the decade-level data, the picture looks even gloomier and confirms the picture I presented in the previous GNXP post: after a fairly steady increase, there is something of a plateau (or perhaps two peaks) lasting from 1885 to 1975, after which there is a 30 year-long plummet to the present.

This recent decline is visible even at the yearly level: you can see the heavily shaded curve dip steadily downward toward the end. In the smoothed 10-year moving average graph, this stands out even more clearly. The peak is around 1984, and there is a steady decline afterward until the latest value at 1998. Now, there are certainly other periods of decline in this graph, but to find one that lasts so long, you have to go back to the decline from roughly 1790 to 1810. And the sheer magnitude of the drop is right up there with the other declines of the past two centuries. Things are not looking so good.

Ignoring the overall rise-and-fall trend, there is an apparent 20 to 25-year cycle, judging from the distance between peaks or between valleys. That's the length of a human generation, although this may be a coincidence. If not, then this would reflect generational changes in how encouraging of innovation the society is -- if they want plenty of cool new things, they may have to trade that off against increasingly monopolistic bodies like AT&T. Conversely, if the zeitgeist is for breaking up corporations that are "too big," the invention rate may suffer. Perhaps the sharp drop starting around 1905 was due to the Progressives and muckrakers.

Whatever the mechanism, it is clear that there need to be at least two groups interacting dynamically -- otherwise we would only see an increase. (This is from the study of differential equations.) Moreover, they need to interact in a way that includes growth and decay terms for each -- rather than, say, one group being gradually converted to the other. I'll leave the modeling aside for now and just note that any good model of invention needs these features.

Even at the level of the centuries-long trend up and down, we need these features. Aside from whatever interactions one generation has with another, which show up on the smaller time scale, it seems that there are two or more groups that people can fall into, and that interact to produce rises and falls over the centuries. For a long time, one of those groups appears to not even exist -- namely, before the Early Modern period. I'm reminded of Greg Clark's popularization of "the industrious revolution" in his book A Farewell to Alms, where English people suddenly became more industrious and future time-oriented, as a prelude to the Industrial Revolution. Under this view, there was a surge in the numbers of smart and hard-working people as the merchant classes genetically replaced the old aristocracy, which killed itself off through wars and feuds, the last of which was the War of the Roses in the late 1400s.

Institutions may matter too. The first patents were granted in Europe during the 15th C., although this requires believing in a century-long lag, given the dearth of inventions during the 15th C. -- it doesn't stand out against the previous 1400 years. At the same time, perhaps the effect took so long because patents -- governmental promises of protection -- mean little unless the state is powerful enough to deliver the tough protection it promised. And they weren't nearly as muscular in the 15th C. as they would become in the 16th.

Maybe it was modern centralized states and the rise of civil servants, bureaucrats, etc., which required new things to keep everything organized and flowing smoothly. Or more likely, it could have been the Military Revolution which began around that time -- the original military-industrial complex. Lots of cool gadgets are the direct fruit of military technology or are barely modified spin-offs (like commercial airplanes).

Whatever the genetic and institutional factors are, it's not hard to tell a plausible story about their decline in the late 20th C. Sure, elite fertility rates had been falling long before then (back to the 1700s in France), but maybe the invention rate is a saturating function of elite population size -- after the elite gets so big, no more inventors will be drawn from it, the rest preferring to go more into law, business, medicine, etc., or uncolonized career fields like community organizer. And certainly the decline in militarism, the skepticism of large state sectors of the economy, and an even greater disgust of monopolistic corporations than even the muckrakers had, all contribute to the decline in institutional support for invention.

Lamentably, the sociological view (even while grounded in individual's behavior) of interacting groups leaves little room for optimism. Given the right conditions on the parameters, the interactions between infected, uninfected, and recovered or immune people when an epidemic sweeps through may spell doom for the disease -- it will flare up but inevitably burn out, and there is nothing we can do to prevent that (a good thing). Of course, changing the parameters to some new combination may result in a qualitatively different outcome, such as the epidemic never infecting most people in the first place.

But we don't even know what the differential equations are that describe how invention changes over time, let alone have good estimates of the parameters involved. Still, gathering lots of data, seeing the rough patterns, and then making mathematical models, may eventually allow us to manipulate the invention rate just as we can affect the course of an epidemic with enough knowledge. That's really all we can do, and whatever extra power over society we get, we get.

from this dataset it's clear that number of important inventions has decreased recently on the year/decade scale. just thinking about it yields the same results: people use the same kinds of devices today as in 1950; the ones used today are just better.

ReplyDeleteit does appear that inventions occur in cycles, and in predictable 25-30 year intervals. you'd have prettier graphs smoothing to a higher order polynomial, and can still preserve features. 9 points, second order, savitsky-golay would probably work well.

many modern inventions are derivatives of other inventions, but consider that large changes in degree can become changes in kind. for example, making computers cheap enough to be used for communication, or internet fast enough to kill broadcast TV can be considered separate function.

another possibility for there not being any recent world changing inventions is that world changing inventions need 20-30 years to change the world. maybe the version 1 isn't all that impressive: cars from the late 1800s weren't very useful and broke down easily; it took decades before the Model T was developed.